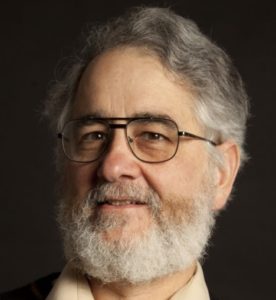

by Robert Lopresti

by Robert Lopresti

Some people become novelists because they have Something to Say. Nothing wrong with that, I suppose, unless they decide to Say it.

Most of us, when nibbling on a delicate little short story or wolfing down a hearty page-turner, don’t want to choke on an indigestible lump of Message. We resent it if the author stops the action to offer a few thousand well-chosen words on an issue close to his or her heart.

I can’t brag that my fiction is always message-free, but I try. So when I recently had Something to Say, I tried to make it a crucial part of the plot.

When I’m not writing mysteries, I’m a librarian at a university. I work mostly with environmental-science students, and love to watch those dedicated folks learning skills to improve the planet. I help them with their research papers, but the real work, like measuring bear poop or improving coral reefs, is not in my skill set.

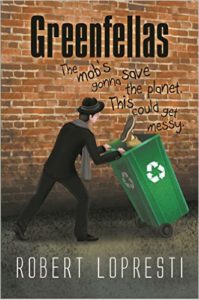

But writing mysteries is. So I dreamed up Greenfellas, a comic crime novel with environmental issues. It’s about Sal Caetano, a top New Jersey Mafiosi, who hears on the news that by the time his brand-new granddaughter grows up, climate change may drown her world. He decides to use his mob skills to save the environment. Personally.

But writing mysteries is. So I dreamed up Greenfellas, a comic crime novel with environmental issues. It’s about Sal Caetano, a top New Jersey Mafiosi, who hears on the news that by the time his brand-new granddaughter grows up, climate change may drown her world. He decides to use his mob skills to save the environment. Personally.

That meant Sal had to learn about environmental problems, which gave me a chance to tell the reader what I thought was important. In short, this was my chance to Say Something.

But how to do what novelists call the “info-dump” without sending the reader into a coma? I could have had Sal sit at a computer for a hundred pages, reading research. Or I could also have hit myself with a hammer, which the reader would have preferred.

Instead, Sal bought a steak dinner for an ecology professor and picked his brain. In a sense, this is a caper novel and you might say my guys are casing the bank, or at least discussing the blueprints.

Which gives Sal the chance to apply his unique view to the issues. For example, the professor says that understanding ecology is “like you put on a new pair of glasses and suddenly you’re seeing things that other people don’t…” Take, for example, the Thanksgiving parade:

“What makes those big balloons float, Sal? What’s in them?”

Sal thought for a moment. “Helium?”

“Right! And how do you make helium?”

“Hell, I don’t know.”

Wally nodded like a bobble-head. “You and the rest of the planet, Sal old pal. You can make it by liquefying air and that’s just about as difficult and expensive as it sounds. Basically, all we’ve got is the stuff we get our hands on when we take natural gas out of the ground.”

“Fracking.”

“Among other ways, yes. But the best guess is we’ll use all the helium up that’s practically available in forty years. About the time your little granddaughter is the age I am now.”

Sal raised his eyebrows. “So they won’t have balloons at the parades anymore?”

Wally slammed his fist down again. Unfortunately he hit his eyeglasses, which tumbled to the floor. “Damn it! If they’re broken…no, they’re okay. Listen, Sal. You ever have an MRI?”

“My wife did. When she got sick.”

“Well, they used helium to make that machine. All kinds of high-tech manufacturing uses helium because it’s inert. That means it doesn’t catch fire, among other things. God knows how they’ll build the machines in forty years. Old Uncle Sam owns one-third of the world’s supply of helium, and by Congressional orders, he’s selling it at fire sale prices, which is why we’re still using it for balloons at kiddie’s parties.”

“But why are you so sure we can’t make more? When we need to, we’ll find a way.”

Wally shook his head. “That’s the Star Trek Fallacy. In science fiction a problem comes up and before the last commercial break some genius has found a brand new way to run the engines on space dust, or cure the plague with margarine. In reality, breakthroughs don’t come on schedule. You see anybody flying around in jet suits lately?”

Both men took a sip at their drinks.

“What ya said about looking at the world through different glasses,” said Sal. “I felt like that my whole life.”

“How so?”

“Well, when I’m with straight people–people who aren’t in my line of work.”

Wally nodded. “Not connected.”

“Bingo. I remember once taking a walk in Newark with Veronica and Maddie. We passed this building site where a skyscraper was going up and they were looking at all the construction and I realized we were seeing different stuff. Completely different. They were imagining what it was like to be up one on one of them girders. I was trying to figure out what percentage of every dollar spent was going to people like me.”

Wally frowned. “You’re in construction?”

“People like me are everywhere, Wally. The rebar, the cement, the drywall, the construction unions, the trash removal… some of those companies we own. From some of ‘em we just get a taste. But on damned near every step there’s at least a thin little slice that went to my people, or somebody like us. I guarantee that.”

“Wow.” Wally pondered. “Sort of an organized crime tax.”

“You could call it that.”

“Is it ever gonna go away?”

Sal emptied his glass. “Right after we get our jet-packs.”

I split my info-dump with scenes of cops scheming to bust Sal. The detectives are warned that “Caetano is out there right now, plotting God knows what sort of malfeasance against the citizens of the Garden State.”

Well, that’s not how Sal sees it. The readers will have to decide for themselves. My job is to keep them interested long enough to find out.

Greenfellas is on the My Favorite Reviews for 2015 list at Kings River Life magazine, available in the January 2016 issue at www.kingsriverlife.com.

Gee, that sounds like a fun book. Clever way to Say Something. Working on a similar scene, too, but the Something is coming from the bad guys – but in a way that the good guys have to concede is a good point.