by Mike Bond

by Mike Bond

All great works of art are thrillers

If a thriller is defined as a book you keep reading to find out what happens next, then all good novels are thrillers.

So is a good poem or any great work of art, be it a painting, sculpture, or music. Any fine work of art leads from initiation through growing awareness to conclusion, and we stay with it not only for the pleasure of each moment, or the greater consciousness and beauty it provides, but also to reach the culmination.

In this regard every work of art mimics the trajectory of life from birth to death, the growth of awareness, the enduring nature of life, and then its end. And every good book concerns the evolution of a person or people, creature or place, the danger they face, a tangled relationship, or some inner demon to be fought. The Bible is a thriller and so are the Upanishads, Greek drama, and The Divine Comedy.

Hemingway, our greatest American novelist, wrote thrillers. Farewell to Arms and For Whom the Bell Tolls both keep us reading by the beauty of their language, the depth of their characters, and the intensity of the lives and issues involved. They capture us so profoundly that we’re carried to the ending, wanting to know if the characters will survive and how will the questions raised in the book be resolved. In both books we don’t know the final outcome until the very end.

Jane Austen wrote thrillers, as did Mark Twain, Balzac, the Bronte sisters, Dostoyevsky, and Tolstoy. As more recently did Nadine Gordimer and Irène Némirovsky, who is one of the greatest French novelists of the 20th century, murdered by the Germans in Auschwitz at the peak of her career. In Albert Camus’s most famous work, L’Étranger (The Stranger), the reader is passionately submerged in the evolution of the tale until the very last sentence, which, as in the case of all great thrillers, summarizes and eternalizes the entire novel.

Let’s take another example, one of England’s greatest poets, Richard Lovelace, known for his lines written in prison, “Stone walls do not a prison make, Nor iron bars a cage.” Nearly every one of Lovelace’s poems is a thriller. It starts with a premise and builds throughout the poem toward a crescendo ending. It is amazing the power he can produce in only twelve lines, as in the case of To Lucasta, going to the Wars, which ends,

“I could not love thee, Dear, so much,

Loved I not Honour more.”

Or for pure astonishing shock, the last two lines of Lovelace’s To Amarantha (check it out).

And another example, Héraklès Archer, the stunning sculpture by Antoine Bourdelle, which like any good thriller starts with the viewer seeing it only one piece at a time, because it is so beautifully complicated we have to read it like a book, from how the archer’s right foot is placed to how he and his bow become united in a powerful tension that is not released until we have understood the entire piece.

Three final examples include Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 3 in D Minor. Like all great thrillers, it opens with a profound and complex first movement that slides into a quieter and more elegiac second movement, then finishes with a truly thrilling and explosive third movement. Or the Eagles’ magnificent Hotel California that builds from the first lines, “On a dark desert highway, cool wind in my hair” through a poetic rendition of the theme toward a final solo that is one of the most beautiful pieces of music ever rendered by the human hand (if you’re a guitarist, try playing it).

Last but not least among all the thousands of great thrilling musical works of recent years, Bob Seger’s Night Moves, which begins simply with the singer’s description of himself and his girlfriend, then of their relationship (“We weren’t in love oh no far from it”), then evokes the connection between a summer thunderstorm and orgasm, then soars to a contemplation of life itself, and coming death: “Strange how the night moves, with autumn closing in,” which summarizes the whole song, the voyage from the creation of life to death, all in barely five minutes.

So with these examples in mind, how do we write a great thriller? How do we create a great work of art?

First of all, we open our minds, our spirits, and our hearts to the full spectrum of life, from the joys of love or parenting to the sorrow of death, the fear of combat, the reflections of a prisoner about to be shot. We do not flinch from reality; we shun political correctness as we would avoid stepping in shit. Political correctness, the refusal to speak the truth for fear of offending or being unpopular or rude, will kill any novel. If your work doesn’t offend anyone, it’s probably no good.

As an example, the protagonist of two of my recent novels, Pono Hawkins, loves women, preferably more than one at a time. This has led to furious condemnations by some PC readers that Pono doesn’t respect women. Yet in fact, he respects them so much he has absolutely no intention of living with just one.

As an example, the protagonist of two of my recent novels, Pono Hawkins, loves women, preferably more than one at a time. This has led to furious condemnations by some PC readers that Pono doesn’t respect women. Yet in fact, he respects them so much he has absolutely no intention of living with just one.

Second, we speak the truth. We don’t need to write silly epics about a situation that will never occur, such a multinational catastrophe based on an impossible premise. We don’t write too much about ludicrous personal choices such as media-soliciting fussiness about some athlete’s change of gender or how hard it was for someone growing up in a different racial structure (instead, write about a refugee’s odyssey from certain death).

Third, read poetry. Not the modern ragtag stuff (as Robert Frost once remarked, writing free verse is like playing tennis with the net down), but real poetry, with rhyme and rhythm building from a simple beginning through a deeper exploration of theme to a final, thrilling resolution. Read it in every language you can; try translating it to understand it (and your own approach to language) more deeply. And read fiction and non-fiction. All the time.

Fourth, live deeply. If we spend all our time in a city, we can’t expect to understand much about life. For most of the last four million years we’ve walked barefoot in the real world, surrounded by the beauty and perils of nature, in close relation with a small number of people. If we ignore or do not live this inheritance, we will write superficially, we will not have our feet on the ground, we will not be down to earth.

This same bias poisons literature today, because most editors (who choose what is published and what is not) live in cities like New York or London. They’re city people, totally out of touch with the natural world (you can’t be in touch with the natural world by spending weekends in the Hamptons or the Catskills, or by a summer trip to Yellowstone). And thus when they do publish works of more rural nature they are often sadly false.

Fifth, conceive the world through others’ eyes. It’s normal to see the world through our own eyes only, but we may be wrong about nearly everything. So imagine someone you don’t like or who annoys you and try to see the world as they do, given how they grew up and in what circumstances.

Sixth, see oneself as a brief cell in the infinity of time and space. To imagine the lives of our ancestors all the way back, from great grandparents to a thousand years ago, ten thousand, a million. To see ourselves, every day, as a compendium of bacteria, nerves, entrails etc., in every detail. When we see another person, to envision them all the way through, from neurons to toenails, not just the face and body they show the world.

Seventh, write about death. Having spent part of my life in extremely dangerous situations, I am drawn to writing about them, perhaps as exorcism for an overwhelming and unrelenting PTSD. No one who goes through a traumatic experience walks away untouched. Thus I find books that go on for hundreds of pages about some person’s emotional situation or relationship, for instance, very boring.

But be careful not to place yourself in danger just to write about it; it’s better to be a bad living writer than a good dead one. So write about your own private journey toward death. But try it also from someone else’s viewpoint, as in Tolstoy’s The Death of Ivan Ilyich.

Many years ago we sat round our Paleolithic fires with the cold darkness and the great unknown at our backs, sharing stories about where to find the antelope herds or how to escape the cave bear or the lion, stories about our ancestors and the meaning of this magical mystery of life.

Rarely do we sit at campfires with danger at our backs, but it’s important to remember those days, and to tell stories about the dangers that stalk us today: Islamic fundamentalism, overpopulation, war, political-corporate corruption, and the desecration of our earthly home. These are the things I write about, and you should try them too.

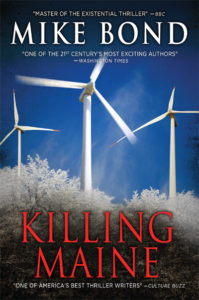

Mike Bond is a best-selling novelist, award-winning poet, ecologist, and war and human-rights journalist. He has been called “the master of the existential thriller” by BBC and “one of the 21st century’s most exciting authors” by the Washington Times. He can be contacted on Facebook at www.Facebook.com/MikeBondBooks or through his website: www.MikeBondBooks.com.

His books include Saving Paradise, The Last Savanna, and Killing Maine.

Copyright © 2015 by Mike Bond